By Joseph Jaramillo

Industrial hemp and psychoactive “cannabis” are the same plant, cannabis sativa, bred and cultivated in very different ways. So if hemp is now legal, shouldn’t “cannabis” be too?

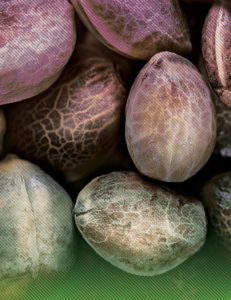

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about the US congress legalizing hemp late last year was how unremarkable it was. Legalization of hemp and its’ non-psychoactive cannabinoid, or CBD, sailed through the house and senate with rare bi-partisan support as part of the 2018 farm bill, which President Trump signed into law while complaining about the border wall. (Trump did turn down Senator Mitch McConnell’s offer to loan Trump his own hemp pen for the occasion.) For hemp farmers and entrepreneurs in the United States, it was a watershed moment. 77,000 acres of hemp are already being cultivated under state protections (half of them in Colorado, which legalized hemp in 2014), and 750 hemp-derived foods and supplements have flooded the $2 billion CBD market. Now that the farm bill is signed, this nascent industry can operate under the full protection of the federal law with access to critical infrastructure such as insurance, banking, and tax write-offs that it had been denied under prohibition. “It’s time to figure it out and see where this market will take us,” McConnell, a Republican, told CNBC, who hopes hemp will replace tobacco as a revenue source in McConnell’s home state of Kentucky. “I think it’s an important new development in American agriculture. There’s plenty of hemp around; it’s just coming from other countries. Why in the world would we want a lot of it to not come from here?” In 1999, the United States began allowing imports of hemp products with less than 0.3 percent of the psycho-active cannabinoid THC, and in 2010 it began allowing limited domestic cultivation of industrial hemp, which was used to make everything from food and body care products to insulation. As consumers embraced hemp foods and demand for CBD surged, more and more states established hemp programs, and production soared in the United States. For all that, the Farm Bill opened up a tangled and confusing conversation when it put the US Department of Agriculture in charge of industrial hemp, which it defined as cannabis with less than 0.3 percent THC; removed the non-psychoactive cannabinoid (CBD) from inclusion in the Controlled Substances Act; and continued the Food and Drug Administration’s oversight of products containing cannabis and cannabis-derived compounds. Hemp cultivation had been illegal largely because authorities in the United States couldn’t tell it apart from psychoactive “Cannabis.” Before the bill passed, all cannabis plants—even those that could not get anybody high—had effectively been outlawed by the 1937 Marijuana Tax Act, which was rammed through the House Ways and Means Committee before members understood what they were doing. Most had not been informed that marijuana, the scary “new” drug they’d been fed so much propaganda about, was in fact hemp, which people all over the world had used as food and fiber for centuries. “That knowledge,” Robert Deitch wrote in Hemp: American History Revisited, “would have killed the Marijuana Tax Act dead in its tracks.” “It is the worlds’ most misunderstood vegetable. No member of the vegetable kingdom has ever been more misunderstood than hemp,” David P. West wrote in a special report for the North American Industrial Hemp Council in 1998. “And nowhere have emotions run hotter than the debate over the distinction between industrial hemp and Cannabis. Though they serve vastly different functions, don’t look alike, and are often referred to as ‘cousins,’ industrial hemp and psychoactive “Cannabis” are actually the same plant, Cannabis sativa, bred and cultivated in very different ways. For centuries, cannabis farmers have understood that when cannabis plants grow close together, they get less sunlight and produce longer fiber-producing stems and no psychoactive resin. To produce plants full of sticky flowers, farmers sow seeds farther apart to give each plant more sunlight and force them to secrete more resin to protect themselves from drying out. Distinguishing between the two types of cannabis plants became important when stricter drug laws were enacted worldwide in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Canadian researcher Ernest Small somewhat randomly tossed out a formula— hemp has less than 0.3 percent THC—that, for no real reason other than his authority as a renowned ethnobotanist 0,3 percent THC became the internationally accepted standard written into most legislation outlawing Cannabis. Earnest Small was merely continuing a taxonomical conversation that dates back to Swedish botanist Carolus Linnaeus, who in 1753 introduced Cannabis sativa, a resilient, prolific plant species he named after the Greek word kannabis, meaning “hemp,” and sativa meaning “cultivated.” When Linnaeus recorded the plant, he documented one species with five variants, launching a debate that rages to this day. Thirty years after Linnaeus recorded C. sativa, French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck introduced what he described as a second “very distinct” species, C. indica, based on plant samples from India. Unlike the tall, lanky C. sativa (hemp) common in Europe, Lamarck described C. indica as smaller and more densely branched, with consistently alternating leaves and a woodier stem that made the plant unsuitable for making fiber. Lamarck believed there were two separate species of cannabis, Chanvre cultive (“cultivated hemp”) and Chanvre des Indes (“Indian cannabis”), which he believed was valued more for its psychoactive effects than its fiber. “The principal effect of this plant consists of going to the head, disrupting the brain, where it produces a sort of drunkenness that makes one forget one’s sorrows, and produces a strong gaiety,” Lamarck wrote, making him the first to suggest a distinction between two separate cannabis species based on C. indica’s psychoactive effects. In a Cannabinoids 2014 article, Jacob L. Erkelens and Arno Hazenkamp explained that Lamarck’s purpose in classifying C. indica as a separate species was to provide a more generally acceptable description of cannabis. “Un-fortunately, the longterm effects of his publication would turn out to do the exact opposite,” they wrote, “and well over two hundred years later we are still left in confusion.” In 1893, the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission conducted one of the most thoroughly investigated, comprehensive studies of cannabis use and culture ever, and commissioners spent considerable time and energy investigating the long-burning question of whether the narcotic-yielding plant (later known as “Cannabis”) was identical to the non-narcotic fiber-yielding plant (later known as “hemp’). They surmised, quite presciently, that inquiring into the longstanding argument about whether C. indica and C. sativa were one species or two would be important in the future because of the possibility that “the restriction of the production of the narcotic by limiting the cultivation may affect a product and an industry which are above suspicion. “The commission based its findings on studies by botanical researcher J.M. Watt relating to the climate, soil, and mode of cultivation, it was rightly concluded that its separation from the hemp plant of Europe could not be maintained.” Watt compared the hemp plant to potatoes, tobacco, and poppies, all of which “seem to have the power of growing with equal luxuriance under almost any climatic condition, changing or modifying some important function as if to adapt themselves to the altered circumstances.” His opinions were replicated by Dr. D. Prain, who observed: “There are no botanical characters to separate the Indian plant from Cannabis sativa, and they do not differ as regard to the structure of stem, leaves, flowers, or fruit. … Hemp, therefore, as a fiberyielding plant and in no way differs from hemp as a narcotic-producing one.” Well, hello. Couldn’t we—shouldn’t we— take this debate to its next logical conclusion now that the US government has bestowed its blessings upon C. sativa and suggest that the plant is legal, regardless of how it grows and what it’s grown for? I’m pretty sure we could find a few botanists who would stand behind that. It’s time to revive this debate.